You are here

Home › Books › The Powers Of The Human Mind Turn Deadly In Craig E. Sawyer’s Novel 'Clay Boy' ›The Powers Of The Human Mind Turn Deadly In Craig E. Sawyer’s Novel 'Clay Boy'

FTC Statement: Reviewers are frequently provided by the publisher/production company with a copy of the material being reviewed.The opinions published are solely those of the respective reviewers and may not reflect the opinions of CriticalBlast.com or its management.

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. (This is a legal requirement, as apparently some sites advertise for Amazon for free. Yes, that's sarcasm.)

It has been said that the human mind is the true final frontier. In that squishy gray matter between our ears originates every earthly idea, impulse, urge, desire and function, and there are those who argue the mind is capable of feats—ESP, clairvoyance, telekinesis—as yet unproven by medical science. Certain esoteric disciplines such as Theosophy teach that human thoughts exist in reality as surely as any tangible object, and remote Tibetan Buddhist practitioners have pushed the notion to its extreme with the manifestation of tulpas, three-dimensional corporeal entities conjured solely through concentration. Such thought-forms, it is believed, may initially act in accordance to their creator’s wishes, but can, and often do, develop their own willful, independent personalities. The idea has spread to Western nations via pop culture, and in the internet age tulpas have become identified with the familiar childhood concept of the imaginary friend, with the users of numerous online forums devoted to so-called ‘tulpamancery’ attempting to generate tulpas of their own.

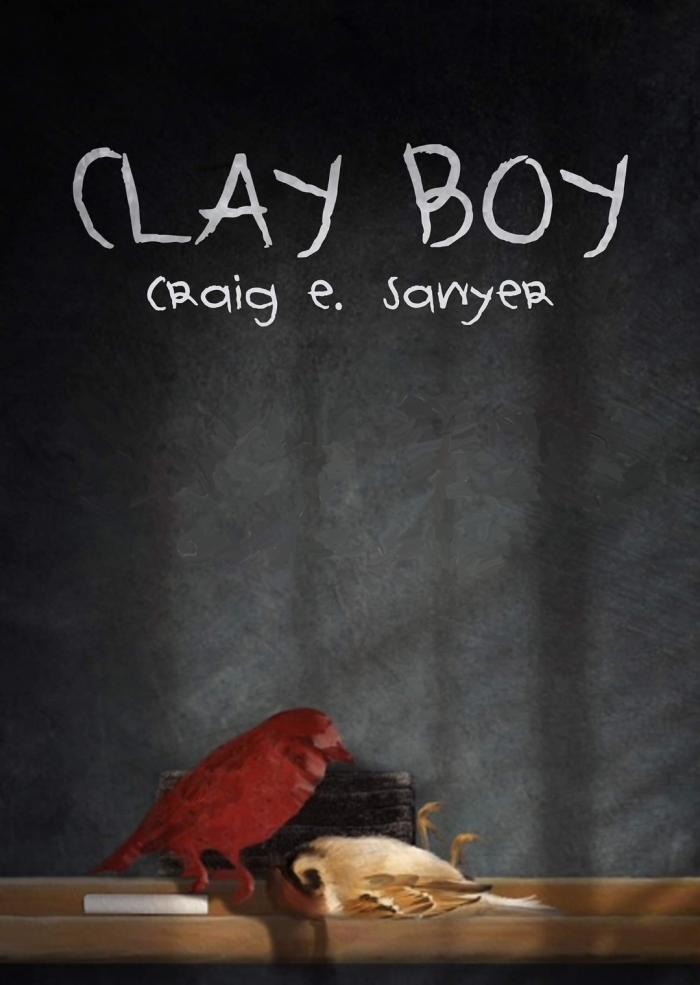

The connection between tulpas, imaginary friends, and the power of the human mind intersect in Craig E. Sawyer’s latest novel, the Brigids Gate Press release Clay Boy. Caleb Jenkins is a middle schooler literally born into trouble; his mother Claire was murdered by a serial strangler stalking the rural roads of tiny Wheeler’s Cove, Tennessee when Caleb was but an infant. Shy, smart and sensitive, the boy grows up a community pariah, at the mercy of both his fundamentalist Christian uncle Nestor, a charlatan ‘prophet’ who exploits the pre-cognitive abilities of his wife to further his backwoods congregation, and the Hyenas, a group of Wheeler Middle School’s tweenage glitterati whose collective pastime is tormenting Caleb for sport. Alone, lonely, and without anyone to turn to, Caleb seeks refuge in his imagination; having been introduced to clay therapy as a way to cope with the emotional wounds left by the loss of his mother, he spends his time crafting vividly lifelike sculptures. After discovering a YouTube video about tulpamancery, however, Caleb inadvertently gives sentience to Gren (short for Grendel), an invisible ‘friend’ who assumes the role of Caleb’s protector. At first Gren’s antics against the town’s wrongdoers are merely mischievous, but when people in Wheeler’s Cove begin dying anew, some suspect Caleb may not be the harmless innocent he appears to be...

There’s a deceptive ease to Clay Boy that belies the skill with which it’s crafted; Sawyer’s story clocks in at 176 compact pages, yet never suffers for the briefness. The novel’s closest literary antecedent is undoubtedly Stephen King’s Carrie; as in that book, Clay Boy focuses on a bullied youth with telekinetic abilities raised by religious zealots who reaps vengeance upon those who’ve sown it. Like King, Sawyer partially relays his story in an epistolary style through newspaper articles, police interview transcripts and excerpts by Caleb’s therapist detailing the boy’s developing tulpamancery, yet what Clay Boy lacks in overt narrative originality it makes up for in other ways; the concept of a tulpa, unlike vampires and werewolves, isn’t yet an overworn fictional trope, and its purposeful connectivity to the Jewish legend of the golem lends the scenario substantial physical menace. The characters, too, are richly drawn: the author displays strident talent for realistic dialogue, such that each actor on his story’s stage has their own highly-developed voice. Wheeler Middle School’s principal, ex-baseball starter Sam Darter, his feisty goth daughter Helen and her would-be video store suitor Donny Myers (called ‘Scares’ due to his penchant for ‘80’s- and ‘90’s horror films) are particularly fun to read, and the author deftly upends overused rural clichés: Caleb’s aunt and uncle, for example, initially portrayed as one-dimensional fire-and-brimstone revivalists, are revealed to be pleasingly complex figures as the storyline progresses. And at the center of the maelstrom is Caleb himself, a complicated boy with an inner darkness molded from years of abuse and pain. His struggles with bullying, depression, loneliness and anger are at once palpable and breathlessly believable.

The weaknesses of Clay Boy are few, though minor ones do exist: the resolution to the Cove Strangler serial killer subplot becomes predictable long before its revelatory denouement, and the novel’s climax, furious, chaotic and satisfying though it may be, is slightly hampered by a sense of open-endedness: an epilogue, even a brief one, informing the audience of the characters’ fates would’ve lent a well-rounded completeness to the plot. It may be that Sawyer has left room for continuing Caleb’s story in future installments; one can hope that is the case, as Clay Boy is a thoroughly enjoyable, inventive and highly entertaining read that earns a well-deserved 4 (out of 5) on my Fang Scale. It will be exciting to see what horrors Sawyer evokes next.