Fear Leads to Codes for Survival in Comics Industry

FTC Statement: Reviewers are frequently provided by the publisher/production company with a copy of the material being reviewed.The opinions published are solely those of the respective reviewers and may not reflect the opinions of CriticalBlast.com or its management.

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. (This is a legal requirement, as apparently some sites advertise for Amazon for free. Yes, that's sarcasm.)

It was a year of turmoil for comics professionals. Livelihoods were on the lines as those who worked in the industry began to see their peers picked off right and left, as the field of comics was being laid waste by the scythe of a force that had found it ripe for harvest. There were rules, arbitrary and unwritten, that had been broken, and the piper had come with the invoice, stamped "Past Due." In a rush of adrenalin-fueled panic, those still standing cobbled together a promissory note, a token to the aggrieved that they would change their behavior, codified for the world to see.

If you think this is a summary of the events of 1954 that led to the Comics Code Authority, it would be understandable. But it's 2020, and the professionals in comics are circling the wagons to protect themselves from threats internal, not external.

In December of 2018, the writer of Vertigo's BORDER TOWN, Eric Esquivel, was released from his duties as a comics writer after allegations were made that he had sexually assaulted a young woman. It could have been an isolated incident -- an industry of fantasists with devoted fans; it was statistically probable that there would 'bad actors' of any sort within that population.

But Esquivel's outing was the spark of a fuse that began to take off within the next year, with accusations levied against Scott Lobdell and Brian Wood. And suddenly it was 2020, and the industry found itself awash in a tsunami of accusations. Cameron Stewart. Warren Ellis. Brendan Wright. Charles Browning. A new name was popping up every day.

It was time for the remaining men in comics to once again develop a code, one they could stamp -- if not on themselves, then on their social media profiles -- to proclaim "This far, no further." Or, to the more cynically-minded, "Please don't attack me next."

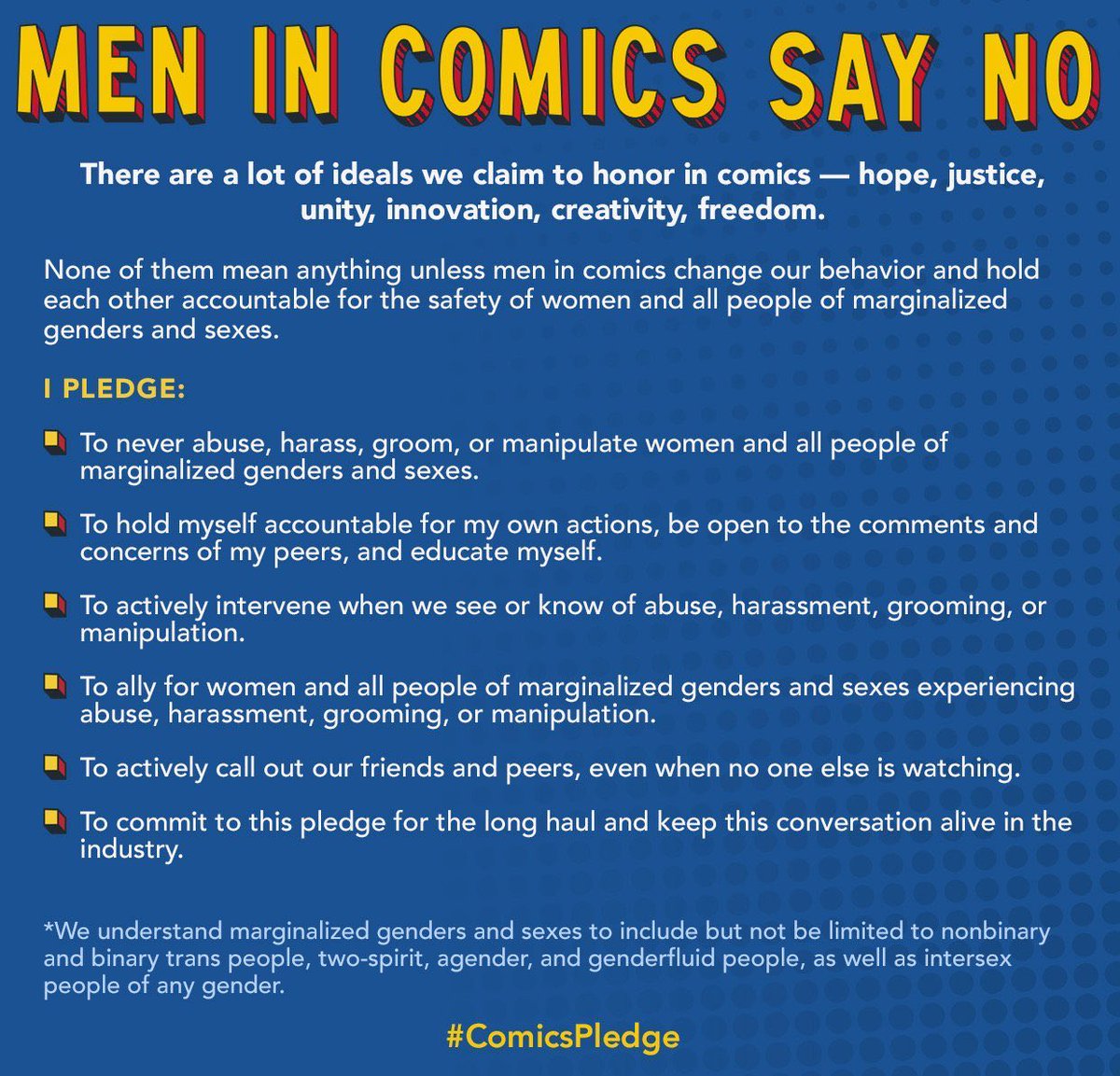

The code, trending on the Twitter hashtag #ComicsPledge, was sent out by numerous comic book professionals.

The Comics Pledge put forth a list of bullet points, making promises to act in certain fashions toward certain groups of people. It was written like a contract, with great specificity and a caveat that veritably screamed that it was virtue signalling -- something that could have been avoided had it simply been a more universal statement in simple language.

Nevertheless, the pledge was reproduced and tweeted by Tom King, Scott Snyder, Steve Orlando, Greg Pak, and a host of others who are either active in the industry, wanting to break into the industry, or are simply fans of comics in general. And in due course, it was also retweeted by those calling it out as an empty gesture -- not just by critics, but by those in the industry to whom the overtures were made, like Cecil Castellucci, who tweeted out, among other things, "Use your quiet: Are you really listening? Do you really think that don’t have to do more than take the #comicspledge?"

The stimulus is different than that experienced in 1954, but the response is the same: a panicked recoil, a curling up into the fetal position while whimpering, "Please don't hurt me." It's a public statement made for the purpose of making a public statement. It's the Pharisee praying aloud while mocking the publican. It has nothing to do with making an internal, personal change that, after thousands of years of religion and philosophy, could ultimately be summed up by Bill and Ted: "Be excellent to each other."